Comments by Dr Paul Szuster, the Strategic Planner, Mentor and Management Educator for an Executive MBA class at Swinburne University, Melbourne:

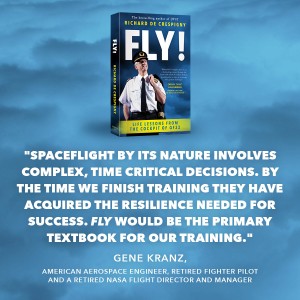

I agree with Gene Kranz’s summary of FLY! (on the back cover).

I agree with Gene Kranz’s summary of FLY! (on the back cover).

FLY! is an excellent text for students in a range of management courses. I lecture MBA units in strategic management, and like your aviation practices in a time of crisis, strategy in business is all about planning with clear objectives to be achieved.

The subject covering organisational behavior has analogies throughout the book. For example, Dr Bruce Tuckman’s team formation theory about teams moving through Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing and Adjourning is highly relevant to management practices.

Acceptance and the handling of change is a fundamental feature of good management.

Throughout FLY!, there are valid references to the need for leaders and managers to handle crises, disruption and change. This is the norm for people in business. It’s not the exception. And that’s why aviators are trained to anticipate unexpected incidents while flying and to develop tactics to handle them.

Finally, neuroscience. FLY! provides an easy understanding of our bodies and mind, and the application of it to management.

Congratulations on crafting such a valuable book for management.

MBA Course: “Delivering Innovation and Other High Risk Strategies”.

The recent Swinburne Executive MBA Course: “Delivering Innovation and Other High Risk Strategies” was tailored for a cohort of local government senior managers working in Victoria. In essence, the course examined risk management theory, techniques and case studies, and their application to the management practices of the students.

In preparation for two sessions, the students were required to read Chapters 4, 6 and 9 from FLY!, watch the ABC’s 4 Corners coverage of the crisis and prepare questions to put Captain Richard de Crespigny.

In the lecture hall the group work-shopped their combined knowledge, and hypothesized on how Captain de Crespigny might have answered their questions.

More information: Management Lessons from the Cockpit by Dr Paul Szuster

Q&A for Captain Richard de Crespigny

Q1 – Knowledge – Shane Power

Throughout your book you reference the works of Sternberg, Thaler and Dunning and the actions of men such as Dr John Taske, Neil Armstrong and Richard Branson (among others). Do you make it your business to be well informed on literature and historic events relating to stressful and or crisis management situations because of your trade, or as a result of your experiences such as QF32?

Shane, in my book QF32 I discuss how I analyse issues from the ground up and research cases to give me the broadest knowledge, applications and defences for all circumstances. This is my continual journey of learning I have embraced throughout my life.

For example:

-

- I researched Fly-By-Wire concepts before I commenced my Airbus A330 conversion course in 2004.

- I analysed the key Airbus accidents-incidents (at Habashiem, Bangalore, Parpignon and even Toulouse) to ensure that I never repeated them myself.

- I researched complex and sensitive topics such as Pilot Induced Oscillations in A330 aircraft.

- I read books by pilots such as Sully Sullenberger (US Airways 1549) and Peter Burkill (BA38).

- I researched and chronicled events in my airline that provided critical learning events. I interviewed Kevin Sullivan, John Bartells and David Princehorn, all Captains in my airline who had managed critical events superbly, to learn the elements of their individual resilience.

A lot of this work was also part of the research I was conducting into technical, and non-technical (Human Factors) topics for my first technical book about Big Jets.

-

- I interviewed aerodynamicists, designers, test engineers and test pilots at Airbus and Boeing.

- I interviewed leaders and engineers at Rolls-Royce factory in Derby, UK, two weeks before the QF32 event.

- This book (Big Jets) has been stalled since QF32 and is now queued for release in 2021.

Every person has their responsibility to commit to a lifetime of learning and change. I do not see my study requirements reducing with time.

Q2 – Why do you think the uncommon occurrence of five pilots in the cockpit worked on this occasion, but may not be the best option in most circumstances.

The more pilots you have in a cockpit, the safer the operation becomes – but only if every pilot knows their role and tasks in the team. If people do not know their roles, tasks, who they are responsible to and who they are accountable to, then order decays into chaos.

Every person must know their role and tasks in their team.

-

- Pilots are trained for all roles, but are scheduled for one role for each flight. There can be many captains on a flight deck, but there is only ever one Pilot in Command who bears full responsibility.

- A team member must only do the tasks for the role they are assigned. Leaders must trust, delegate to and then leave the other pilots alone (and not micro manage them) to do their tasks.

- Pilots should monitor each other and if necessary, manage “downwards” and “upwards”. But communications must be prioritised to prevent distractions. I discuss the necessity for monitoring at (FLY! p212 and QF32 p169)

- The Pilot In Command is responsible for their team, all decisions and the outcome.

Forming. In the bus on the way out to the airport before flight QF32, I briefed the operating pilots to ignore the check captains, who were not part of my team, and not to let them distract us from our mission. I made clear every person’s roles. (FLY! p204) & (QF32 p142).

Storming I called STOP! (Storming process) to reiterate the roles of two supernumerary pilots at the beginning of the flight. (FLY! p208–10) & (QF32 p148)

Q3 – Managing Upwards and Leadership – Scott

A common theme in the book relates to how Richard takes on feedback and objections from his crew and creates a collaborative environment in the Cockpit. Yet in the heat of the moment on QF32 he made the decision to enact the Armstrong Spiral despite objections from his fellow pilots – what determines the threshold of when his ideas as a leader override those in the cockpit?

I discuss the Armstrong Spiral at FLY! pages 98, 159, 230 and 238. Down to my core, I knew that I was ultimately responsible for the lives of the passengers and crew. I would be the only person responsible if someone died. This sense of responsibility increased my determination to act to ensure every person’s safety. I had studied the Armstrong Spiral years earlier and it was part of my intuition. I had the intuition (trained decision – gut feeling) that knew it was the right thing to do at that time.

Follow up: How long did this determination take (i.e. after X amount of years his confidence in his experience determined how to assess the ideas and objections?)

Follow up: How long did this determination take (i.e. after X amount of years his confidence in his experience determined how to assess the ideas and objections?)

The Armstrong Spiral was intuition, based initially on training, especially my first flight in the Macchi jet at RAAF Base Pearce in 1989 (QF32 p171).

Read FLY! page 126 for the times the brain needs to make decisions.

-

- Practicing actions makes habits that can execute rapidly (for sounds within 20 ms, for sights within 60 ms), subconsciously and about half a second before we are aware of them. (FLY! p23) This time difference is why (for example) we signal the start of a running race with a gunshot rather than a light.

- Practicing decisions build intuition (or gut feelings) that can be recalled subconsciously within a few seconds. (FLY! p18, 126, 157-8, 160-3)

- Un-practiced (non-intuition) complex decisions take at least 30 seconds to complete.

Q4 – Crisis Management – Stuart

I was keen to ask Richard about how he felt Rolls Royce handled their PR during the aftermath and also dig a bit deeper about models/processes for supporting complex decision making.

I think Rolls-Royce missed an opportunity to communicate with the public, using the knowledge it had at the time to take control of its crisis, keep people informed and protect its brand. That’s what is needed in the critical first Golden Hour, except the Golden Hour is now gone.

In 63 per cent of crises, the company expected its crisis because in 80 percent of the crises – they caused it. So, when the crisis hits and every victim with a phone becomes a journalist, the leader must get on-site, and COMMUNICATE (disclose the truth, protect the brand, commit to doing something to allay fears, be empathetic and give their personal guarantee (FLY! p81)). All these things build teamwork, trust and protect the brand.

If Rolls-Royce had followed the examples of Richard Branson (Virgin) (FLY! p 86, 175, 277), Johnson & Johnson during the Tylenol crisis or done things resilient companies do in crises (that I describe in FLY! (chapter 4) (, then it would have emerged from the crisis with a better brand than the brand it had before the crisis.

Rolls-Royce leadership might have been worried about avoiding the PR disaster that plagued BP during its handling of its Deepwater Horizon disaster (FLY! p74, 150–1, 166). If that was the case, then I think it was Rolls-Royce’s mistake. Rolls-Royce probably thought that BP’s CEO said too much. In fact, Tony Hayward, the CEO was on site quickly after the explosion. But it was not that he said too much, rather he was un-empathetic repeating to the media. “I’d like my life back” many times. (FLY! p74) After the crisis, Haywood became “the most hated and clueless man in America” (Ref A p234) and BP came close to collapse. (Ref A p206)

The truth is that The Deepwater Horizon was (in my opinion) an accident waiting to happen because BP exhibited little if any of the elements of corporate resilience.

Rolls-Royce is an excellent company with a remarkable and honourable history that simply made a chain of unfortunate mistakes. I still hold the highest respect for the Rolls-Royce company and it’s engines.

There are many models for decision making that suit different occasions and I imagine most are correct. The model you use is a personal preference. I detailed the decision models I used during QF32 at FLY! (p 138).

If you wish to research decision making in greater detail, then I recommend books by Gary Klein, a research psychologist famous for his work about decision making.

Reference A: Spills and Spin by Tom Bergin

Q5 – Crisis Management – Matthew

Had you made contact or received direction from executive or senior managers within Qantas before you made the decision to deliver a full debrief to the passengers?

No. And curiously, some people were surprised that I was not disciplined by my managers for debriefing the passengers!

I knew I had to debrief the passengers, despite it not being a company-industry procedure or requirement.

When fear takes hold, perceptions become reality that quickly spread like a virus. In today’s world where everyone with a phone is a journalist, you must gather those affected in a crisis, take control and stop fears, rumours, innuendo and panic spreading like wild-fire.

When disaster strikes, leadership must be present, responsible and empathetic. Even if the crisis is not your fault, when your reputation is founded on safety, then you must take the lead and protect people’s safety – at any cost. Be transparent, disclose the facts, give a single point of contact and your personal guarantee. (Case studies: Tylenol – 1982, Boeing – 2019)

It’s for all the above reasons that I gave full and Open Disclosure (FLY! p79–84, 91) and my Personal Guarantee (FLY! p81) .

I have given my personal guarantee four times whilst on duty with the A380. The first time was during an overnight delay to a service I was commanding in 2010. The second occasion was during the QF32 event. The most recent time was 18th March 2019 after a major delay to a service due to a mechanical failure in London. There has only been positive reactions to my giving a personal guarantee – never a negative.

Q6 – Risk – Shane Power

You refer to the theory of micromorts. Given your experiences such as QF32, do you approach your job and other activities with greater caution or fear?

No. Everything I do is based upon risk. Risk is factual and rational, and I am driven only by facts I try to avoid dread (irrational risks-fear) and give risky endeavours the respect they deserve.

Everyone must be able to identify, rate and live with risk:

-

- Identify threats. My Chronic Unease (FLY! p108–9) and deference to expertise (FLY! p85) gives me ample opportunity to identify most threats I need to analyse before embarking on a new project. Once a threat is analysed, you must calculate the risk.

- Risk = Probability x Consequence (fine detail: When plotting risk, use logarithmic scales for both axes so that constant risk appears as straight lines)

Once the risk is calculated, be sensible and accept only risks that satisfy your risk appetite (FLY! p 145, 284) and avoid unnecessary and higher risks:

-

- Every accepted risk must be mitigated (otherwise it remains a gamble).

- Only insure what you cannot afford to lose. I insure my house and wife, but I do not pay for costly loss-of-flying licence insurance, because I have created a few alternate careers if I must leave flying.

- As a general rule, avoid gambles (FLY! p 146, 150, 164), especially the gambles that kill.

My ability to calculate risks gives me the confidence to avoid unnecessary risks and the courage-fearlessness to embark on many risky-profitable-beneficial ventures. I only take on high risks only if there is a commensurate reward.

The MicroMort (FLY! p147) is a great way to compare the risks of mortality and can be used to justify things you decide to do/avoid:

-

- I wrote that the MicroMort risk (of dying) from one hospitalisation is the same as risk as dying in 70,000 one-hour commercial airline flights. So I am happy flying in my airline anytime. I think splitting your family up to fly different commercial aviation flights is being too risk-averse given the MicroMort risks involved.

- My Mother and Uncle were killed by simple clinical errors in hospitals. I avoid hospitalisations at every opportunity, and suggest patients leave hospital at their earliest opportunity. (I wrote a long risk analysis of different hospital treatments that if people are interested, I will publish at a later time)

If you are interested in the study of risk, then I recommend you read “The Black Swan, or “Fooled by Randomness” by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Q7 – Risk – Louis

During the crisis on Flight QF32 what was in your mind the worst-case scenario and what were you prepared to risk, ie your risk appetite?

During the crisis on Flight QF32 what was in your mind the worst-case scenario and what were you prepared to risk, ie your risk appetite?

Great question!

The greatest threats were fuel exhaustion and wing internal fire- which had the highest risks. The lesser threats were the flight controls and aircraft handling.

-

- The mitigation for fuel exhaustion was to climb (to enable an Armstrong Spiral).

- For a severe and continuous wing fire, the only mitigation is to immediately land or ditch, if too long (in time) from a safe landing strip.

High risks existed and persisted for failures in other remaining systems, and how we might be able to use them effectively. I chose to stay airborne, to do threat and error management (FLY! p145), that is identify the threats, prevent them happening, fix them or mitigate them. We then had to discover what we had left on our electric, automated aircraft, and then learn how to best use these systems and resources to land.

The flight control checks confirmed our mechanical and flight performance and mitigated many subsequent risks. Research El Al Flight 1862 for more information. That is why the flight control checks (QF32 p219 242) were the most important things I did on QF32. (I write about flight control behaviours, saturation, pilot induced oscillations and flight control checks in my next book on Big Jets).

Know your risk appetite. Be confident, courageous and fearless to enforce it:

-

- My risk appetite has no ceiling during a crisis. I would gladly risk the US$440m A380 airframe and every insurance policy to avoid death. I would risk my life to save others’ lives. I am not sure, but I suggest that Captain Sully Sullenberger had the same priorities during the Miracle on the Hudson. Some pilots incorrectly consider risking passengers’ safety to save their airframe. During a crisis, the aircraft is only a tool to me. I never put a dollar figure on saving lives during a crisis.

- Remember: Be legal. If you can’t be legal then be safe. If you can’t be safe then be ethical. Always act so that later, you can stand in a court of law and say you acted to maximise safety and to do the right thing.

After the flight, I now realise the greater threat we faced was losing just one more wire in that (cluster bombed) left wing. If it turned out that we did not have thrust-control of number 1 engine, then, if you work sequentially through the extended logic, the outcome would most likely have been different.

Q8 – Human Factors – Tim

Richard, your stories and experiences from the QF32 crisis are as much about human thoughts, decisions and actions as they are about mechanical or computer failures. Air crash statistics suggest that human error is one of the biggest contributors to aircraft disasters. The opposite can be said about QF72.

Yes, human error is reported to be the biggest cause of aircraft disasters – but this is a misleading statistic.

First, aircraft are getting harder to fly.

Automation does not make aircraft easier to fly – it makes them harder! Automation does repetitive things with high accuracy, but when the closed, complex black box systems fail, and black-box systems degrade other black-box systems, the resulting broken automation leaves the new generation pilot controlling a huge complex machine with little support. When automation fails on the A380, the 4,000,000 parts and 853 passengers are dependent upon the actions of just two pilots – one more than the pilot of the Wright Flyer in 1903.

The problems with automation for every person, is that it creates:

-

- Automation Amnesia,

- Automation Dependency,

- Complacency,

- Over-confidence, and

- Dislocation and ignorance.

These are insidious problems for everyone. For example, do you know how to turn off your “press to start” car while travelling down the highway? No person I have asked does. All car drivers should read this article. slate.com/technology/2019/03/boeing-737-max-crashes-automation-self-driving-cars-surprise.html

Resilience in high-tech environments requires all operators to know their systems down to their foundation technologies, so that these operators can manually take over safely when the automation fails. Automation is not perfect. Automation often fails. And when the automation does fail in aviation, it’s up to the pilots to recover the operation and keep it safe.

The statistic in your question is therefore misleading because, it turns out that in most fatal aircraft accidents, a failure occurred first in the automation that the pilot was unable to recover from. The start of the error vector in many crashes is the machine, not the pilot. Pilots may be a contributory factor in most aircraft accidents, but what is not identified is that pilots routinely save aircraft every day after automatic systems fail.

Q9 – Disruption – Tim

Do you believe that AI systems will completely replace human inputs in years to come? And if so should we trust computers to take control of risk management related decisions in the midst of a crisis?

Future intelligent systems will have real (not artificial) intelligence. They will do everything a human can do, including making and learning from mistakes. Future machines will also have unlimited (networked and fused) sensors, processing power and memory. These machines will perform at a rate probably a million times faster than humans. Anything a human can think and communicate, should be able to be done by a sentient (thought, awareness, consciousness and prediction) machine.

We will see the first basic sentient machines within 20 years that will assist with and challenge our lives. In one application for the elderly, sentient robots will prevent humans becoming lonely, and thus improve our mental and physical resilience. Ultimately, sentient machines will be capable of managing risks in a crisis. Sentient machines will be fully capable of flying aircraft.

Sentient machines pose as much a threat to humans as they pose opportunities. They will be a disruption to humans, but the time of sentient machines will definitely come. When the next war erupts and you are ordered to provide a warrior, would you prefer to offer your son/daughter or a robot?

The key to disruptions is to disrupt yourself, keep control and not let others disrupt you and take control from you (FLY! p269). The key disruptors humanity faces are listed at FLY! page 280. You cannot block these disruptors, so learn, adapt, change and harness rather than repel them. My next career after flying will be building and working with sentient robots.

If this answer depresses you, then please read Enlightenment Now (FLY! p 279) and Factfulness, (FLY! p 279). These two books explain how our world, that has been steadily and progressively becoming more automated over the past 200 years, is a better place today than it was at any other time in human history. There has never a better time to be born, alive and active than today.

The future world will be better than the world is today. It will be led by passionate, tough, competent, disciplined and resilient people who can execute. Be guided by the Kranz Dictum (FLY! page 189).

Ensure you are one of them.

This page updated 18 March 2019